From Lottery to Ladder: Toward a Wage‑Weighted H‑1B System

What Happened

The Department of Homeland Security issued a proposed federal rule that would fundamentally change how H-1B visa registrations are selected, moving from a random lottery system to a weighted selection process that favors higher-paid workers. While framed as a technical adjustment to better serve congressional intent, the change represents a fundamental restructuring of how America allocates access to foreign talent – with implications that extend far beyond immigration policy.

The current system is that H-1B registrations are selected through a random lottery when applications exceed the annual cap of 85,000 visas (65,000 regular + 20,000 advanced degree exemption). Because this process is based on chance rather than merit, candidates are not guaranteed an H-1B visa unless their registration is selected. For example, a software engineer at a three-person startup has the same probability of selection as one at a Fortune 500 company.

For advanced degree holders (U.S. master’s or higher), the process operates in two stages. First, these candidates are entered into the 20,000 visa advanced degree pool. Any advanced degree candidates not selected in this stage are then entered into the 65,000 regular cap lottery. Consequently, holding a U.S. advanced degree increases the likelihood of selection but does not ensure it, as the outcome ultimately depends on random selection.

What Changed

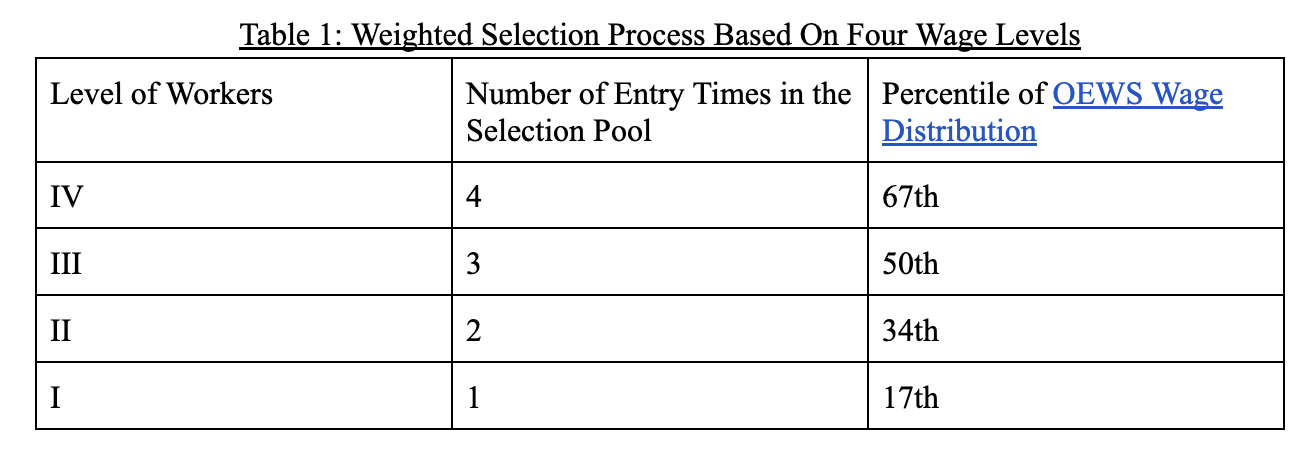

The proposal essentially introduces a weighted selection process based on four wage levels set by the Department of Labor:

DHS argues that this change better aligns with Congressional intent for the H-1B program to attract “higher skilled and higher paid aliens” workers. According to DHS, current data shows Level III and IV workers (those earning at or above median wages for their occupation) are underrepresented in the current H-1B selections. The agency believes that one way to identify skill levels is through compensation, as higher wages generally indicate greater expertise. Accordingly, the agency maintains that “salary generally is a reasonable proxy for skill level”, citing research by the Economic Policy Institute that supports the correlation between wages and worker skill.

Under the proposed rule, employers would face additional requirements when submitting H-1B registrations. Specifically, they must indicate the wage level of the offered position, the Standard Occupational Classification (SOC) code corresponding to the job, and the intended work location. When filing H-1B petitions, employers must ensure that the information matches the registration and provide supporting documentation to justify the claimed wage level. This measure is designed to maintain the integrity of the selection process: USCIS would have the authority to deny or revoke petitions if it finds that employers attempted to manipulate the system—for example, by inflating wages during registration to increase selection odds and then lowering them after approval. These requirements aim to ensure that the weighted lottery accurately reflects the intended skill and wage criteria.

Examining the Underlying Assumptions

The proposal rests on a critical assumption: that compensation level reliably indicates both skill and economic value. This assumption, while intuitive, merits closer examination.

Consider two positions with identical skill requirements but different compensation structures. A machine learning engineer at an established technology company might earn $140,000 (Level IV), while a comparable engineer at a venture-backed startup might earn $95,000 plus significant equity (Level II). Under the proposed system, the first candidate would have four times the selection probability of the second, despite potentially equivalent contributions to innovation and economic growth.

This disparity reflects not differences in skill or value, but differences in business model, funding stage, and risk tolerance. The weighted system may inadvertently privilege certain types of employment relationships over others—specifically favoring established corporations over emerging ventures.

Why It Matters

The following table summarizes registration and selection data for fiscal years 2021 through 2026, with selection rates calculated separately:

A notable observation from the chart is that, since 2024, most categories—with the exception of “Eligible Registrations for Beneficiaries with No Other Eligible Registrations” and the overall “Selection Rate”—have shown a declining trend. This suggests a gradual decrease in the number of total registrations or active participation in certain registration categories over recent years, while the lottery’s relative probability of selection has remained more stable. This is mainly due to three reasons: USCIS policy changes, specifically its move to a beneficiary-centric lottery, fraud investigations and enforcement, and economic and labor shifts, especially in tech sectors.

The introduction of a weighted selection process for the H-1B visa could further influence these trends by altering the probability of selection across different registration categories. Unlike the purely random lottery, a weighted system would prioritize certain applicants based on criteria such as wage level, employer type, or advanced degrees. This shift is likely to benefit large corporations, which can afford to offer higher wages and have established hiring practices aligned with the weighting criteria, thereby increasing their chances of securing H-1B approvals. Conversely, small businesses and startups may be disadvantaged, as they often cannot match the wage levels or resources of larger employers, potentially reducing their selection rates. In fact, DHS provided statistics on this: “DHS estimates that the proposed rule would result in a significant impact on 5,193 small entities, or 30 percent of the 17,069 small entities affected by the proposed rule. DHS considers 30 percent as a substantial number.” DHS added that small entities that seek to hire higher-earning employees may also benefit. However, this argument is not supported by evidence demonstrating that small entities have the capacity to hire such employees at the same level as large corporations.

Broader Significance

The DHS estimates that this proposal could have significant economic effects. It projects an estimated quantifiable economic benefit of $502 million in the first year, rising to $2 billion annually by the fourth year, as higher-paid H-1B workers gradually replace lower-paid ones over time. The proposal would also create an additional administrative cost of $30 million per year for employers.

About 30% of small businesses that file H-1B petitions are expected to experience a noticeable economic impact, mainly those hiring employees at the lowest (Level I) wage tier. In terms of industry impact, the rule would affect computer and mathematical occupations as well as architecture and engineering fields. Computer and mathematical occupations make up 69% of H-1B petitions, and the effect is expected to be mixed because many of these positions are at Level II wages. For architecture and engineering, the rule could have negative effects for civil engineers and architects, who are mostly Level I, but positive effects for engineers in higher-paying roles, such as materials engineers.

The Innovation Ecosystem Concern

Beyond immediate selection statistics lies a more fundamental question: how does this change affect America’s innovation capacity?

Research consistently shows that immigrant entrepreneurs have founded a disproportionate share of high-growth companies [1][2]. Many of these founders and talented individuals entered the United States on H-1B visas before starting their ventures. Examples include, not limited to, Elon Musk who is the world’s first man to ever worth half-trillion, Eric Yuan who is the founder and CEO of Zoom, and Satya Nadella who is the chairman and CEO of Microsoft [3]. A weighted system that channels foreign talent primarily toward established corporations would significantly reduce the pipeline of potential founders who gain experience, build networks, and identify opportunities while working in the U.S.

This represents not merely a redistribution of existing visa allocations, but a potential shift in entrepreneurial activity. If highly skilled immigrants increasingly work for large employers due to structural selection advantages, the rate of new venture formation by foreign-born founders may decline accordingly. This, in the long term, will lead to a decrease in America’s innovation capacity, eventually a declining economy.

In conclusion, the stakes are clear: fewer startup success stories, slower innovation, and a tech sector increasingly dominated by companies that can afford to pay their way to the front of the line. Employees in these big companies might see more structured hiring processes and potentially higher compensation. This may influence job opportunities, salaries, and the pace of innovation in industries like tech and engineering, especially, ultimately affecting what products and services are available and how quickly they develop for the general audience to use.

[1] “New Report Shows How Immigrant Entrepreneurs Create Jobs Across the U.S.” American Immigration Council, September 9, 2024. https://www.americanimmigrationcouncil.org/press-release/fortune-500-2024-report-immigrant-entrepreneurs-create-jobs-across-united-states/.

[2] Dizikes, Peter. “Study: Immigrants in the US Are More Likely to Start Firms, Create Jobs.” MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology, May 9, 2022. https://news.mit.edu/2022/study-immigrants-more-likely-start-firms-create-jobs-0509.

[3] Yeo, Dylan Butts, Victoria. “From Elon Musk to Microsoft’s Satya Nadella: Tech Leaders That Were Once H-1B Visa Holders.” CNBC, September 29, 2025. https://www.cnbc.com/2025/09/29/from-tesla-to-microsoft-satya-nadella-tech-firms-leader-once-h-1b-visa-holders.html.